How to Get Quoted in The New York Times.

Yes, there is luck involved, but with the right prep you can increase your chances.

I know this sounds a little crazy, but when reporters call me, I have to remind myself to talk like a normal person.

Academics aren’t trained to speak clearly. We just aren’t. We’ve got our own vocabulary and standards that just don’t translate very well to everyday conversations about important events.

So when I am asked to explain my research to someone outside of a lecture hall, it feels like I’m translating it into a different language. It would be easier—for me—if policy makers would just google my articles and books and read them on their own; but we all know that isn’t going to happen.

Over the past few years of working the the Scholar Strategy Network, I’ve come to terms with the fact that no one outside of academia is going to consider what I have to say unless I deliver it to them in their preferred format and style. Right now, for me, the best way to do that is through existing media outlets that already have well-established audiences.

Subscribers to Everyday Realities may remember a post I wrote about how it took “48 hours of Work to Get 90 Seconds of Airtime on the Today Show.” In that piece. I tried to explain what it is like for an academic to work with video news reporters. In this post, I’m going to go into more detail about working with text news reporters and what it takes to get quoted.

For a video interview, academics can negotiate with producers on how to select visuals or backdrops that help tell the story. When working with text news reporters, scholars have no say over formatting or accompanying photos. Instead, researchers need to narrow down their analysis into tightly worded phrases that convey much larger ideas. This requires a different kind of prep.

But the effort can be worth it. Getting quoted by name in a national publication is usually a once in a career occurrence for most academics, so when I got an email with an @nytimes.com address out of the blue, I knew I had to jump on it.

And it worked!

Last week, I was mentioned in “Just Miles from Kroger’s Court Battle, a Food Desert Shows What’s at Stake”

The quote:

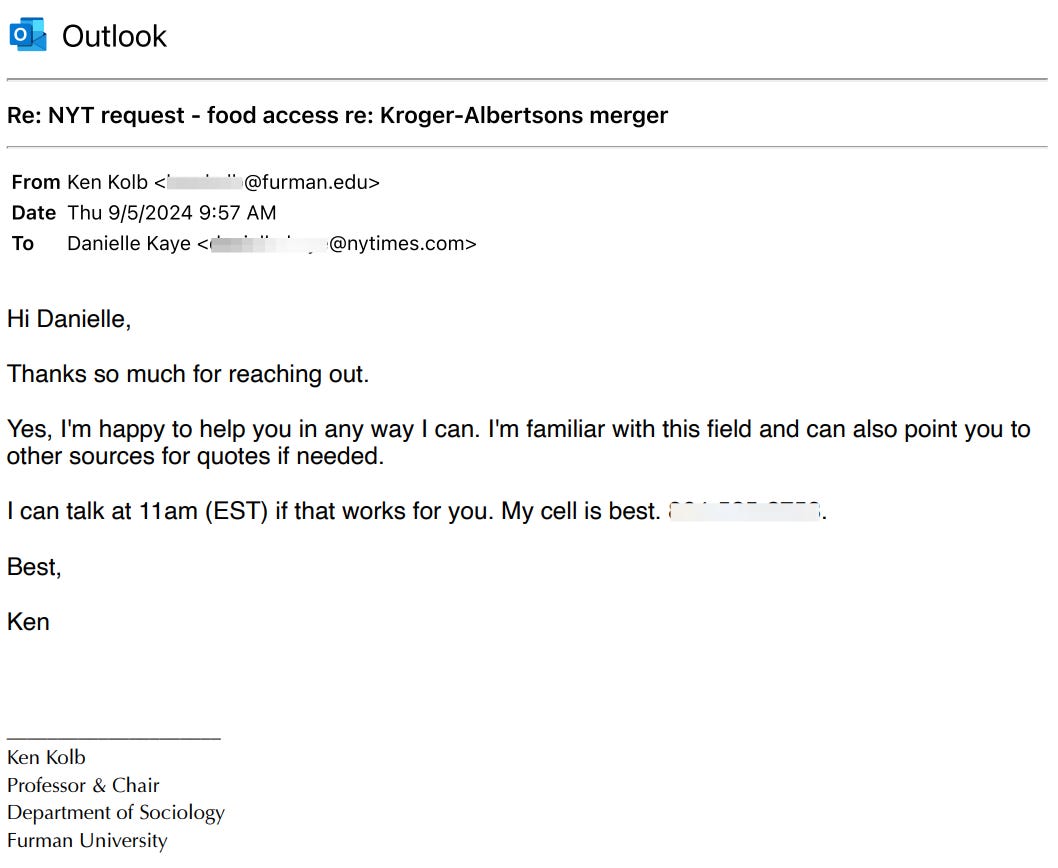

The email:

To explain the process of how this all happened. Let me start from the beginning.

Last Thursday, at 9:14 am, I got an email from Danielle Kaye, a business reporter from The New York Times.

After reading the email, I knew I was an expert in this area. I wanted to be interviewed. But I also knew I would need to prepare before I did so.

There was just one problem. The reporter wanted to talk that morning. And I was already in the weeds.

The work of a department chair is neither glamorous nor especially hard. It is really just a lot of little things that have to get done. But my to-do list that day was a bit longer than usual: I had teaching, grading, a regular check-in with the dean for an hour, and then another hourlong department meeting in the afternoon. And both of those meetings would require their own prep. So this wasn’t a good morning for a phone call.

But again, it was The New York Times, I needed to make time.

So, I didn’t reply to the reporter’s email right away. I had to get my thoughts together and put together a little strategy.

The prep:

I asked myself: What can I add to this story? What hasn’t already been said?

To answer those questions, I needed to get up to speed on the Kroger-Albertson’s merger. As always, my go to source for all things food retail is Errol Schweizer. He’s got a great newsletter, The Checkout, that you should, well, check out. He’s written extensively on this topic.

So I scanned his latest writeup on the merger and put together some ideas on how I could offer a new perspective. Whereas most of the debate about the Kroger-Albertson’s issue has focused on the business side of the grocery store industry, my research focuses on consumers.

I research the innovative ways households decide to get to and from the store as well as how they decide what to buy when walking the aisles. As most already know, their shopping decisions are shaped by price of goods and proximity to stores, but I specialize in analyzing how the dynamics within a household, like work schedules and number of kids, determine what people actually eat. These everyday decisions seem simple, but the “kitchen-table economics” of any family is more complex than you think.

Now that I had a strategy, I gave myself about an hour to prepare. I emailed the reporter back and asked for an 11am call.

Then I got to work: I started listing some talking points that applied my past research to this case. Then I started compiling some stats and figures to answer questions she might have, like how many households experience food insecurity in 2023 (13.5%, up from 12.8% the year before). By 10:45, I was ready.

The call:

It’s 11:02 am.

The reporter called my cell phone. Danielle Kaye explained her beat and what she had been observing in a suburb of Portland, Oregon. I’ve spoken to a lot of reporters about this topic and I could tell right away that she knew her stuff, which made my job much easier.

She asked some basic questions about my job title and where I work, and then asked for an overview of how food retail came to leave many American communities behind. I took this as my cue to launch into a primer of how the “food deserts” of today were created by highway and housing policies of the past. This turned out to be a mistake.

As I was talking, I could tell I was losing her attention. She gave me some verbal hints that I was telling her stuff she either already knew or that was not what she needed. When a reporter tells you: “that’s really interesting, and I might be able to write a longer piece about this one day, but if you could give me your thoughts on….” That’s code for “please get to the point, I have a deadline.” Message received. From then on: I tried to keep it short and to the point.

I decided it was best to focus on what I knew best that could also add to the debate. My research focuses on the point of view of shoppers. So, I stuck to my talking points.

The talking points:

Talking Point #1:

Q: When a Store Closes, Who Suffers the Most?

A: The “Near Poor”

Although it is tempting to believe that the poorest are the most affected by a store closure, that actually isn’t the case. Fewer retail options for those living in absolute poverty—the destitute—does not change their shopping calculus because they weren’t full participants in the retail food market to begin with: they rely primarily on donated food. For the extreme poor, even if they lived next to a grocery store, they couldn’t afford to buy all their food from it anyway.

The people who are most affected by a store closure are those who live just above the poverty line. These households have just enough money to buy all the food they need in a month, but are a flat-tire away from their lives spiraling into despair. This income bracket is what the Census calls the “near poor” and they live at 100%-200% of the poverty line (for a family of four, that means earning between $31,000 and $62,000 a year).

The reason the “near poor” are the most affected is because a store closure means having to travel farther to get to the next supermarket, which incurs costs in both time and money. While they could chose to shop at convenience stores nearby, those are more expensive, so they will likely end up paying more (bus fare, gas money) to get to the next nearest supermarket. And that extra expense will cut into their already tight food budget.

Those who live above 200% of the poverty line (family of four earning more than $62,000) are still inconvenienced, but they already had options. Even the lowest earners in this category are still on the verge of middle class, likely have access to a vehicle, and almost definitely have someone in the household with a job. When their closest grocery store closes, they still pass by other supermarkets on their way to work, to run errands, or to pick up their kids from school. Shopping farther away costs them extra time and money, but, like the majority of Americans, they likely didn’t shop at their nearest grocery store in the first place.

This is why the “near poor” are hit the hardest.

Talking Point #2:

Q: Why can’t a smaller “Community Market” Replace a Lost Supermarket?

A: Those on the edge of poverty depend on one-stop shopping.

I spent over a hundred hours interviewing people at their kitchen table as they grappled with shrinking food options. The loss of a supermarket is a demoralizing experience for any community. The departure of good quality retail (supermarkets, banks, pharmacies, hardware) signals to those who live there—and those passing through—that their community is losing out relative to other areas of town.

What makes the departure of good retail so painful is that it produces a vacuum that is typically filled with bad retail (liquor stores, pawn shops, payday lenders). People shop at bad retail out of necessity, not preference. Its presence has been a sore spot for many communities for decades and even those who frequent bad retail are frustrated by their neighborhood’s inability to attract better shopping options.

When a grocery store closes, communities typically respond in patterned ways. First, they call upon their political leaders to recruit a new store to fill the vacant space, pushing them to use tax breaks and subsidies as incentives. These efforts sometimes work. However, there is no guarantee that the new store they begged to come will stay when its incentive package expires. Just ask the residents of Spartanburg, SC about the Piggly Wiggly that took in $1 million in grants and loans to open a store, only to close within a year.

If a community can’t recruit a supermarket, they usually try to organize smaller ventures such as a small sundries store, a non-profit neighborhood market, an urban garden with vendor space, or maybe even a mobile farmers market. All these ideas are well meaning, but none replace a supermarket. If these initiatives sell fresh foods, those veggies will assuredly cost more than what people can get at Walmart. And everyone needs toilet paper. So residents ultimately wind up making a big trip to a Supercenter anyway at some point in the month where all the fresh foods being sold at much cheaper prices.

So, unfortunately, many community retail food interventions, no matter how well intended, typically fail. It’s sad. I’ve catalogued dozens of these closures. Even when residents want to support non-profit endeavors, they simply can’t afford to do so in the long run. Bigger supermarkets—even if farther away—still offer the lower costs, greater variety, and fewer trips per month that families need. Put simply, “one-stop shopping” is an economic necessity for many.

The big picture:

So what does it take to get quoted in The New York Times?

Some luck and a good bit of work. I spent 30 minutes on the phone trying to explain points #1 and #2 as clearly and plainly as I could. From that material, the reporter pulled a catchy quote and distilled my entire argument into 71 words. Frankly, I was grateful for what I got. If people want to learn more about what I have to say, well I wrote a whole book on the subject.

At the end of the day, I don’t know if I’ll ever be quoted in The New York Times again. But if I get another cold call or email, I know I’ve got a process on how to respond. Getting quoted isn’t a random outcome. It requires work. But if you are an academic and you want to get your ideas out there, it’s worth the effort.